Free hearing evaluations at the CUW audiology clinic reveal more than meets the … ear.

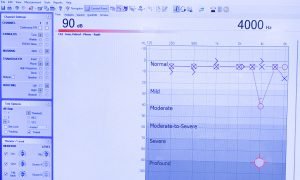

I had long been aware that I don’t hear quite as well out of my right ear as my left, and now I have confirmation. What I hadn’t imagined, however, was that the “deficiency” is only in a narrow range of frequencies. Approximately 4,000 hertz (4 kHz), to be more precise.

The loss isn’t severe enough to warrant any sort of hearing aid, but that particular frequency range is where conversation takes place. So it could mean I have to listen a little more closely to hear people talking when there’s background noise, such as in a busy restaurant.

This is what I learned when I had my hearing checked at the Concordia University Wisconsin audiology lab by Dr. Kim Sesing—much in the same way students learn to check hearing at the weekly free hearing evaluations the lab offers. These sessions were started as a way to let students get practicum time on real patients, but have the added benefit of offering a valuable service to members of the Concordia community.

“It really is not even a required experience, but we feel it’s an important aspect of the program,” Sesing said. “Speech, language, and hearing are very closely connected, so all of our students take a semester’s worth of audiology practicum in their graduate program.”

Ingrid Rich (’20), a graduate student in the speech-language pathology program, confirms that it’s a valuable educational opportunity.

“Throughout the course of the semester, I was able to work collaboratively with Dr. Sesing and my peers to administer hearing screenings and audiometric tests to Concordia faculty members, students, and alumni,” Rich said. “These experiences allowed me to apply knowledge in meaningful ways. They also reinforced the importance of determining an individual’s hearing status to ensure that they have the means to effectively communicate in a variety of settings.”

(Students at CUW interested in pursuing a career in this field start with a bachelor’s degree in communication sciences and disorders, then go on to earn a master of science in speech-language pathology. Audiology is a four-year doctorate program that is not offered by CUW at this time.)

The original plan was to offer testing to a wider community, but when COVID-19 hit, the team decided to keep things in-house to start. Fortunately, the response was good and Sesing was able to fill most appointments all year long. Some additional sessions will be offered this summer, and plans are in the works to expand the program in the fall, depending on how things go with the pandemic.

Cutting-edge Equipment

The program is blessed to have state-of-the-art facilities in the Robert W. Plaster Free Enterprise Center on campus. A lot of Sesing’s colleagues at other schools are envious, she says, because so often hearing centers are tucked away in some room in the basement. The CUW audiology lab is new, brightly lit, and offers glorious lake views.

“We’re very fortunate that our program started at the time this building was being built, and they really took into account the presence of our program,” Sesing said. “We have this south end of the building, all three floors, for speech-language pathology. It’s a beautiful audiology facility.”

The booth is designed to keep out external noise, and you can hear the acoustic difference the moment you walk in. Everything suddenly sounds dead. The test itself is relatively simple. Various tones are played through headphones, at different frequencies and volumes, and you raise your hand when you hear one.

In my case, the test included a second part. Sesing came in and put a different apparatus on my head, one that delivered the sounds through the base of my skull instead of my ears. This was to confirm, she later explained, that it wasn’t wax in my ears that was causing my issue (some wax is actually good, she said, as long as there’s not too much of it).

She had told me that when nothing is wrong a test might only take 15 minutes. When mine stretched beyond that, I thought something might be up. That second piece of head gear added to my suspicions. The results she showed me on the screen confirmed it: My right ear does not have a good working relationship with sounds in the 4 kHz range.

On the plus side, it was easy to understand everything she was telling me, thanks to the nice big touchscreen display in the booth. She was able to cycle through various charts and graphs quickly and easily, which added visual clarity to my audiology results. A screen like that is something else most labs don’t have, Sesing said.

Issues like mine are precisely what the tests are designed to detect. Most people don’t have their hearing checked on a regular basis, Sesing said, and they often don’t notice when it starts to deteriorate. Getting a regular check can help you be more aware when your hearing starts to go downhill—before it starts to become an issue for others.

It’s very common for people not to notice their own hearing struggles, Sesing explained, even when it’s plain to others that there’s an issue. Often people with new hearing aids will comment, “This is so much better! I had no idea my hearing had gotten so bad.”

And now I’m determined not to let that happen to me!

An Ear Toward the Future

Sesing said my particular loss is somewhat unusual, and likely caused by some sort of trauma to my ear. She asked if I fired guns, and I said not really. I’ve fired a few at camps over the years, but always wore proper hearing protection. But later I remembered spending time years ago with some family up north. We did some skeet shooting and went duck hunting a couple of times. (I got one with my very first shot!) And I don’t recall worrying about ear protection. Hmmm …

But that’s just one possibility. Sesing said it could also have been the result of an ear infection, or some other trauma many years ago that I don’t remember. In any case, it could be congenital, something I was born with, though a genetic defect would usually show up in both ears.

She also asked when was the last time I had my hearing checked. Maybe in grade school, I said. She nodded knowingly. Most people don’t ever have it checked unless they detect a hearing issue. The problem with that approach, she explained, is that now I have no baseline to see if my issue is a new one—or if it’s getting worse over time. So she put me in the system for a follow-up appointment in six months or so.

I was fascinated! Never can I recall being so excited about discovering a physical defect in myself.

I was glad that it wasn’t serious, and the whole process made me think about how it must be a great relief to have a problem diagnosed. Even better when you then discover there is something you can do about it.

And that’s why I’m going to go back when the time comes. In the meantime, if I happen to shoot any guns, I’ll be sure to wear proper ear protection. Maybe I won’t sit so close at the fireworks on the Fourth (if they have them this year). And if someone says something I don’t want to hear in a crowded restaurant, I’ll say, “Sorry, can’t hear you! That’s my bad ear!”

If you are interested in taking part in a hearing clinic, limited spaces will be available on Monday afternoons this summer. Contact Kim Sesing at kim.sesing@cuw.edu for details.

To learn more about earning a bachelor’s degree in communication sciences and disorders or a master of science in speech-language pathology, visit cuw.edu.

— This story is written by Mike Zimmerman, videographer/photographer for Concordia University Wisconsin. He may be reached at michael.zimmerman@cuw.edu or 262-243-4380.

If this story has inspired you, why not explore how you can help further Concordia's mission through giving.