This story first appeared in the fall 2018 issue of the Concordian, the official magazine of Concordia University Wisconsin.

In 2007, while studying as a graduate student at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Christopher Cunningham, PhD, discovered a new class of potentially non-addictive opioid analgesics that brought scientists one step closer to the “holy grail” of developing safer painkillers. Years later, in the height of the nation’s opioid crisis, Cunningham and his students are continuing the quest. He’s one of several Concordia professors whose passions and expertise are driving a culture of discovery.

In 2007, while studying as a graduate student at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Christopher Cunningham, PhD, discovered a new class of potentially non-addictive opioid analgesics that brought scientists one step closer to the “holy grail” of developing safer painkillers. Years later, in the height of the nation’s opioid crisis, Cunningham and his students are continuing the quest. He’s one of several Concordia professors whose passions and expertise are driving a culture of discovery.

Christopher Cunningham, PhD, was sick of hearing about his favorite musicians dying. As a self-described child of the ’80s, Cunningham was raised in a suburb of Washington, D.C., on MTV and came of age as the Seattle music scene was exploding in his living room. A budding musician himself, Cunningham was drawn to the heavy guitar riffs with a punk flare and the raw, personal lyrics distinctive of the bands coming out of the Pacific Coast at the time. The “grunge” music style and subculture had captivated America’s youth and compelled teenagers everywhere to wear flannel shirts and army boots, grow out their hair, and take music lessons so that they could be a part of the movement.

Related: 9 impressive research efforts underway at Concordia

As the grunge subculture was making its way through mainstream young America, so, too, was heroin. Heroin, also known as diamorphine, is an illegal opioid derived from the opium poppy plant that’s mainly used as a recreational drug for its known euphoric effects. It’s a Schedule 1 substance, which means that it’s highly likely to be abused.

While heroin has been in the United States since the late 19th century, three main factors contributed to its resurgence in the early 1990s: the drug had become cheaper, purer, and available in powder form (as opposed to injections), so it was more accessible and acceptable in middle-class America. Influencers in art, music, and fashion became early adopters of the re-established drug, and were so effective in their advocacy that American culture redefined beauty to replicate the look of a user—emaciated, pale, and tired— the look that became known as “heroin chic.”

While heroin has been in the United States since the late 19th century, three main factors contributed to its resurgence in the early 1990s: the drug had become cheaper, purer, and available in powder form (as opposed to injections), so it was more accessible and acceptable in middle-class America. Influencers in art, music, and fashion became early adopters of the re-established drug, and were so effective in their advocacy that American culture redefined beauty to replicate the look of a user—emaciated, pale, and tired— the look that became known as “heroin chic.”

This phenomenon played out in rural and urban America, in the streets of Seattle, and on the television in the Cunninghams’ living room and every other living room across the country.

One by one, Cunningham’s music heroes were struggling with and dying of heroin related causes. First it was Andrew Wood from the band Mother Love Bone, then Kurt Cobain from Nirvana, and then Shannon Hoon from Blind Melon. And the deaths would keep coming.

Cunningham, the son of a chemist father and educator mother, gave up his instruments and channeled his fascination for grunge music and culture into a life mission to find answers and create solutions to the heroin epidemic that was taking so many artists so soon—a quest that continues today, with a promising research breakthrough under his belt.

He followed in his parents’ footsteps and enrolled at the University of Maryland in College Park to study chemistry with a desire to teach. Upon graduation, Cunningham enrolled at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy in Baltimore, and, fortuitously, under the tutelage of Dr. Andy Coop, professor and associate dean for academic affairs, would make a discovery as a graduate student that would be an effective first step in his quest.

“It just so happened that Dr. Coop was at that school asking the same questions that I was,” says Cunningham. Questions, like: Could we develop opioids with less-addictive qualities? Why does the effectiveness of opioids drop over time when used to treat severe pain? What can we do to prevent more people from dying from these drugs that help people?

The student and his mentor honed in on the question of consistent effectiveness, and focused their research on the concept of tolerance. According to Cunningham, “When a patient becomes tolerant to the analgesic effects of a painkiller, the physician must increase the dose to compensate.”

This increase is likely to cause the patient to experience other consequences, like severe constipation, addiction, and possibly even overdose.

Cunningham and Coop were the first to propose that this tolerance was due to a protein in the brain called P-gp (P-glycoprotein or multidrug resistance Protein 1). P-gp is an important drug flusher that significantly impacts the patient’s ability to absorb, distribute, metabolize, and excrete toxic substances. In other words, “The job of this protein is to throw drugs out of the brain like a bouncer would throw rude customers out of a nightclub,” explains Cunningham.

Hundreds of compounds, hundreds of failures, and one lab fire later, the chemists eventually developed the compound that could prove their theory correct. This compound was more potent than morphine at killing pain but was able to avoid detection by P-gp (avoid getting “bounced” out of the brain). “This is a pretty big deal, because P-gp plays such an important role in how so many drugs work. If we can avoid P-gp, we might be able to get significant pain relief without the devastating side effects,” explains Cunningham.

Their collaboration led to a significant finding that’s still being tested today.

After earning his PhD, Cunningham joined the Department of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas, where he met his wife, Allison. In 2011, the couple moved to Wisconsin where Cunningham accepted the position of assistant professor of pharmaceutical sciences at Concordia University.

At Concordia, Cunningham attacks the opioid crisis from three different angles: He teaches, mentors, and advocates.

As a teacher, his primary focus is teaching medicinal chemistry to PharmD candidate students. He teaches students to understand how drug structure affects its function. In other words, individuals respond to medicines and dosages differently, so pharmacists not only need to know the medicine, but they also have to know the patient.

“Every aspect of drug action—whether it is taken by mouth or in a patch, taken once a day or twice a day, even if it cannot be taken with grapefruit juice—is tied directly to its chemical structure,” says Cunningham. “My job is to make sure students are prepared to counsel patients or consult industry on the foundations of drug action.”

Cunningham’s second focus as a teacher is in drug design for students enrolled in the master of product development (MPD) program. In this role, he prepares students to work in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries by teaching them about the process of turning an idea into a medicine, with a goal of inspiring students to make life-changing discoveries.

As a mentor, he works in the lab alongside students at the undergraduate, Pharm.D., and MS levels on team-based projects related to drug design and discovery. One team is working on developing non-addictive painkillers that are showing significant progress in early testing. Cunningham shares that they aim to tackle the “Holy Grail” of painkillers: developing an agent that treats pain but is non-addictive, doesn’t cause constipation, and avoids overdose.

A second team is developing treatments for amphetamine and synthetic cannabinoid abuse. While opioids are getting the headlines, synthetic man-made drugs—like methamphetamine and “bathsalts”*—are also being heavily abused in America, particularly in the Midwest. According to Cunningham, treatments for these drugs don’t yet exist. He and his student pharmacists are trying to be the first to treat this emerging crisis. They’re working on antidotes for these stimulants similar to how NARCAN ®** counteracts the effects of opioids in the human body. Like his other discoveries, this antidote is showing early promise.

As a community advocate, Cunningham is a popular speaker who openly and candidly fields science questions about the brain’s biology, painful questions about addiction and recovery, and lighthearted questions about his taste in music. As the crisis in America grows, so, too, do the crowds at his talks.

While it was the tragic loss of famous people that lured him into pharmacy, Cunningham finds his greatest motivation in his conversations with everyday people. “It doesn’t matter who they are or where they come from,” says Cunningham. “People are struggling with very heavy things and desperately want to understand addiction. I want to learn more about the brain so that I can help more people, more families in need.”

Brief History of Heroin

While opium has been in the United States since the early 1800s, the heroin compound was created in the late 19th century. It was thought to be a more powerful, non-addictive pain reliever, and its usage was widely embraced by the military to manage the pain from war-related injuries. Upon discovery of the devastating effects, heroin use was banned in the United States under the Anti-Heroin Act of 1924. That set the black market in motion, and the drug has been making its way illegally into the country ever since. Between 1965 and 1970, there were an estimated 750,000 heroin addicts in the country, prompting President Nixon to create the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1973 to consolidate resources to fight the heroin problem.

Though initially effective in slowing heroin and opium abuse, other recreational drugs began to emerge, including powder and “crack” cocaine in the 1980s. When heroin and prescription opioid abuse roared back in the 1990s, it infiltrated all forms of culture, and its usage has been on the rise ever since.

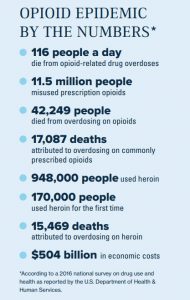

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioids killed a record 42,000 people in 2016. In 2017, President Donald Trump declared that our national opioid crisis is a public health emergency. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services unveiled the Five-Point Opioid Strategy that focuses on improved access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services, as well as improving data and research.

The spring Concordian hit mailboxes the week of October 1. View a PDF version of the magazine here. If you are not on our mailing list, but are interested in receiving a free copy, call (262) 243-4333.

— Lisa Liljegren is vice president of marketing and strategic communications.

If this story has inspired you, why not explore how you can help further Concordia's mission through giving.